"Dark matter", invisible as it is, makes up 90% of the universe and is what caused the big bang. Artist-theorist Gregory Sholette has brilliantly used this phenomenon to describe the thousands of us who work within art praxis but never get recognition in an attempt to articulate the politics of this missing mass. "The oversupply of artistic labour is an inherent and commonplace feature of artistic production." (1). But does it have to be like that?

On May 8th 2021, the project space OnCurating and the association FATart organised an art protest in Zurich, aiming to reclaim the cultural surplus of the "missing mass" which gave the name to the initiative.

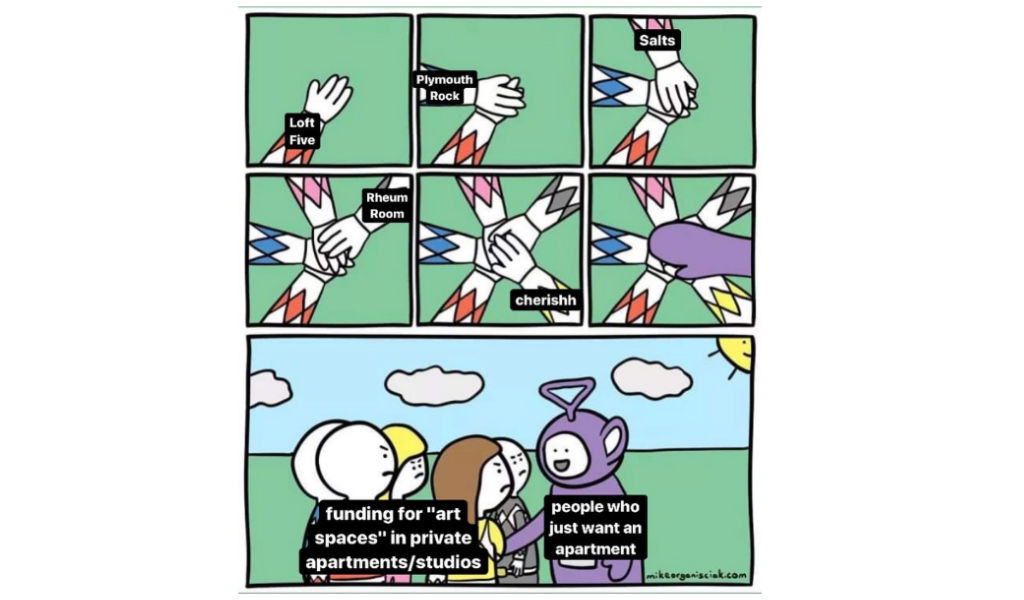

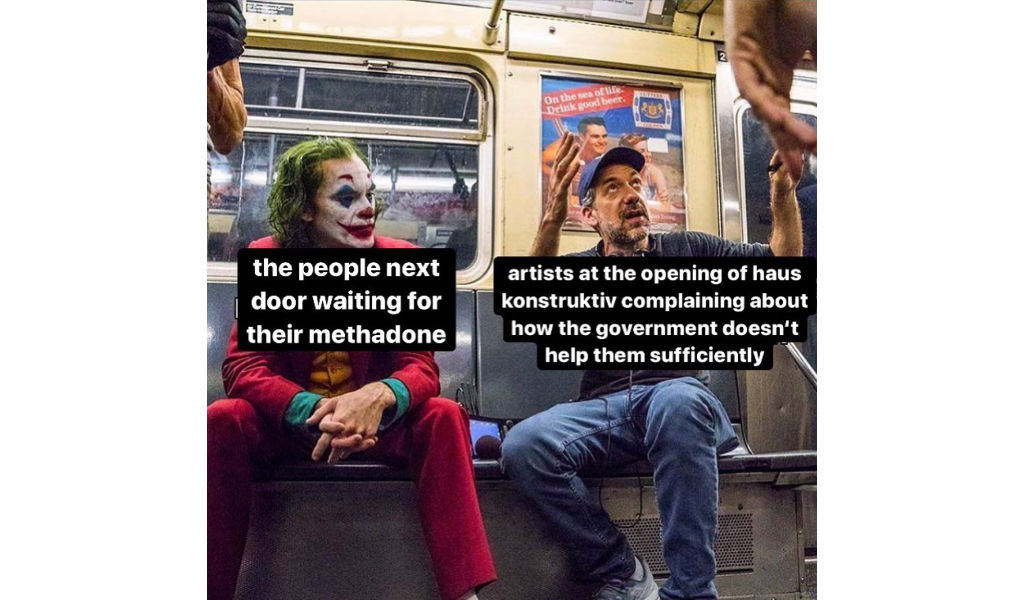

As mentioned on a previous occasion, there is no homogeneous art scene in Zurich. Even within artist-run spaces and project spaces, huge differences coexist: some operate in close structural comparison to traditional galleries; others favour discourse and are built around an artist community and special shared interests. Others still are closer to partying. Nevertheless, they all compete for the same funding from the city, the canton (region), and other private supporters (2). Those who are part of this scene often know each other well, and some projects even collaborate, like in the case of OFF-OFF, networking for initiatives of the independent art spaces (3). Then there are the big institutions, like Kunsthaus, Kunsthalle, and Haus Konstruktiv, which are extremely well funded. The creative industries are an enormously important business sector in Switzerland. In Zurich, and with Art Basel close by, the extremes of contemporary art come together pretty visibly and in close proximity. Even if a precarious situation is relative in Switzerland, the clash is there since most people receive some social security and health insurance.

Marina Vishmidt affirms, "there is a connection between the contradictions of the social development of artistic labour in capitalism and the formation of the aesthetic subject in modernity as the displacement of labour from the category of art, bringing it into closer affiliation with the speculative forms of capital valorisation." (4). These considerations seem to apply perfectly to Zurich as an axis: capitalist accumulation of surplus from the arts, dealing in high-priced art, underfunded free artistic and curatorial work, and, what Vishmidt analyses as, new formations of subjectivity that are enabled and enable the economic system of neoliberalism.

Like its astronomical cousin, creative dark matter also makes up the bulk of the artistic activity produced in our post-industrial society. However, this type of dark matter is overwhelmingly invisible to those who claim the management and interpretation of culture: the critics, art historians, collectors, dealers, (certain) curators and arts administrators. On the other (dark) side stand the young, the recently graduated, those working in "informal" practices such as home-crafts, makeshift memorials, internet art projects of various types, amateur photography, Sunday-painters, self-published newsletters and fan-zines, me writing this article and so on. Yet, just as the physical universe is dependent on its dark matter and energy, so too is the art world dependent on its shadow creativity in much the same way certain developing countries secretly depend on their dark or informal economies. After all, to acknowledge it would undermine its own privileged concept of artistic "value." It is here that Reclaim the Cultural Surplus! (RCS), with its rhetoric slogans, colourful banners and strike-vibe come into play on an otherwise lazy Saturday afternoon.

The most undeniable flaw of the initiative is the poor attendance at the protest in front of the Kunsthaus considering the pertinence of the causes' issue to a majority of the citizens involved in one of the biggest sectors in Switzerland.

I can spontaneously hypothesise different factors connected to Realpolitik, the very practical and less ideological Swiss way of being. Firstly: it could be that although involved in the independent scene, in the depths of one's heart, one actually hopes to be part of the other faction one day. Secondly, and this is less speculative and more often heard: many artists received financial support from the government during the coronavirus pandemic and don't dare to complain for the old reason "others have it worse" and in this case, "few have it better". There is also the attached concern that this facility could go away, potentially worsening their already precarious situation.

Sholette makes the sophisticated argument that precarity, while not desired, is its own best motivator: "Useless labour develops its own economy from which to persist, linking methods of making art as social production to itself as a product of its circumstances, much like the aesthetics of Arte Povera or feminist rejection of art history, which presumed male-dominated creation, materials, and subjectivities of high art and reflected the politics of art processes, hierarchies, and so forth." (5)

There is more to the production of art than is evident in the commercial art world. We all know it. Considering a "territorial" structure of "centre/periphery" in comparison to the "astronomical" structure of dark/light matter a pyramid is a less useful metaphor. Since the dark matter does not propose a simple opposition between centre and periphery, but moves instead within, or in-between, the meshes of the consciousness, discourses and institutions as a residual agency of artistic hopes, possibilities, failures, ideas, project applications. It is akin to what Georges Bataille described as a "principle of loss," a pathological economy of expenditure without precise utility (6). However, perhaps there is much deeper complicity between the two components/opponents?

Before one begins to speak about "political art," or "interventionism, to cite Lucy R. Lippard and Nato Thompson respectively, one must first understand that there is a political struggle at the level of production. Or, as Slavoj Žižek quipped, "It's the political economy stupid!" (7)

For us as artists and cultural workers, it comes down to using our potentially transformative power to develop a viable counter-narrative that, bit-by-bit, gains power within the larger public discourse of what art historian Carol Duncan describes as the "natural" condition of the art world (8). We need to ask how to use this vibrant inert mass to intervene within the political economy of culture understood as an everyday form of production. In the already quoted article, Vishmidt pins down the basic difference between "regular" work and artistic work. She sees that art is not under the rule of real subsumption—and therefore cannot be subsumed under a comparable general demand for a wage. Real subsumption means that capital gradually transforms all social relations and modes of labour until they become thoroughly imbued with the nature and requirements of capital, and the labour process is subsumed under capital (9). I think such works offer sites of (potential) resistance and autonomy since they are not perceived as "proper art" and remain liminal to cultural capital's expropriative tendencies.

How does one learn to embrace not only an agency that is socially generated but also the active or inert resistance of a specific urban space or history?

Considering that Sholette's book was published in 2010, the concept of missing mass has evolved over the last ten years. Dark matter is getting brighter, involving cooperative networks and forms of collective production that are inherently unsettling to mainstream notions of aesthetic privilege, hierarchical authority, and individual success.

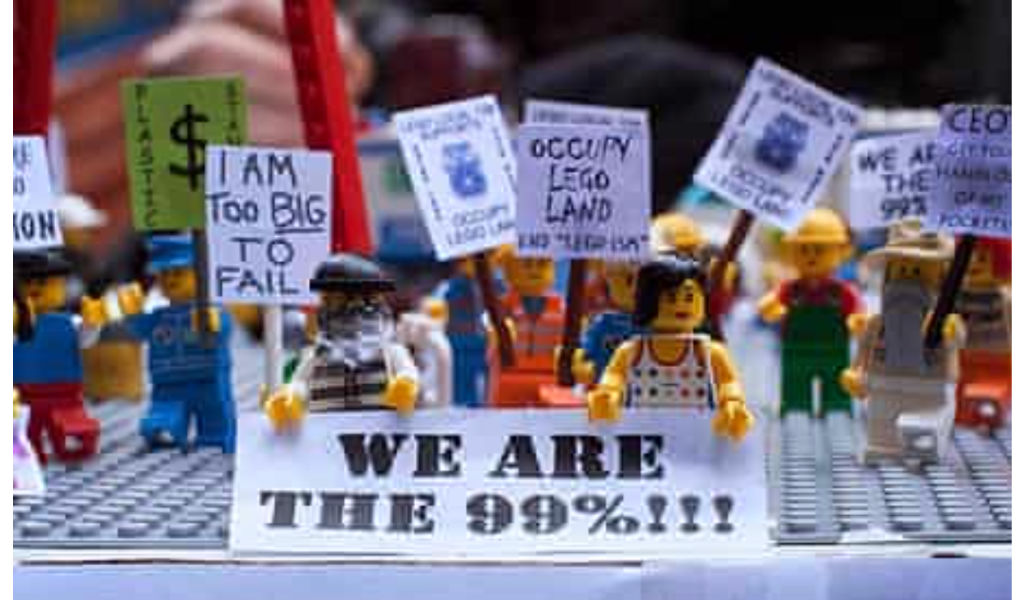

The Occupy Movement started with the Puerta del Sol in Madrid in 2011, then caught fire across the Middle East, lit up Wall Street's Zuccotti Park in New York City, and so on. Yet also those creative class cognitariats have now sadly entered the surplus archive of a dark matter's history from below. However, as these protests propagated, they dramatically re-imagined political agency and labour suddenly returned as an issue. In an act of faith in the transformative potential of art activism, Sholette writes, "it is a process of recovering what the past has betrayed' (10). Not all protesters (and nowhere near enough in my opinion) think this position necessarily positive. Some groups are progressive or pro-democracy but are permeated with reactionary, regressive elements. Some people imagine their collective bodies grounded in a solidly reconstructed and glorious past, like several examples we can all think about in politics. Loss of alternatives is the worst because it forces us to go back to the past to look for examples that have already proved to be failures, in a sort of toxic nostalgia.

For his 2016 documentary HyperNormalisation (11), Adam Curtis borrowed the word Russian historian Alexei Yurchak used to describe the Soviet society when everyone knew it was fake but accepted it as normal. A sense of atrophy and repetition. The updated version is contained in the striking first sequences of his film:

WE LIVE IN A WORLD WHERE THE POWERFUL DECEIVE US

WE KNOW THEY LIE

THEY KNOW WE KNOW THEY LIE

THEY DON'T CARE

WE SAY WE CARE

BUT WE DO NOTHING

AND NOTHING EVER CHANGES

IT'S NORMAL.

The frustration for this post-truth normality is well conveyed by Curtis' words on investigative journalism's trend: "When you tell me that a lot of rich people aren't paying tax, I'm shocked, but I'm not surprised because I know that. I don't want to read another article that tells me that. What I want is an article that tells me why, when I'm told that nothing happens and nothing changes. And no one has ever explained that to me." (12)

What is called for now is a grammar of cultural dissent not willing to turn innocently away from the chaotic and delirious state of contemporary social realities or the contradictions of dark matter within a world of bare art. In an imagined dialogue between Curtis and Sholette, the latter would reaffirm: "It needs a critical analysis that recognises this moment, this perilous moment, as ultimately historical in nature, and therefore also as a time and conflict that will one day be displaced, as all such moments are. One significant weapon in this battle is the difficult and continuous collective development of the dark matter archive from below, that redundant agency made up of surplus memories and marginalised hopes." (13)

The "collective development" is exactly what I think could be the turning point of the whole discourse. "Unlike normal matter, dark matter does not appear to interact with the electromagnetic force. Researchers have been able to infer the existence of dark matter only from the gravitational effect it seems to have on visible matter." (14)

We want to be individuals who express ourselves and are in control of our own destiny. With the rise of hyper-individualism in society, that sense of being part of a movement that could challenge power and change the world has been replaced by a technocratic management system. But we're not that individualistic; we're actually very similar to each other. Furthermore, it looks like the only reaction to the dark matter can occur through acts of collectivism.

Of course, the relation between radical, transformative practices and art institutions can't be simply reduced to oppositional terms. "Amnesia attacks and ongoing reinventions of the wheel", writes Lucy Lippard, "are two things that have plagued social activist art and the left for as long as I can remember" (15). How might our narrative about art social practice be set differently? Sholette situates this commitment as part of a potentially, more long-lasting, solidarity "..is art's occasional venture into radicalism something perhaps an inescapable phase of an aesthetic investigation that ironically must jettison aesthetic investigation itself? Must it be the case that, when artists take their turn on the barricades, along with the partisans and oppressed, the dispossessed and the evicted, they are there because, aside from playing for the enemy, they simply have nowhere else to go?" (16)

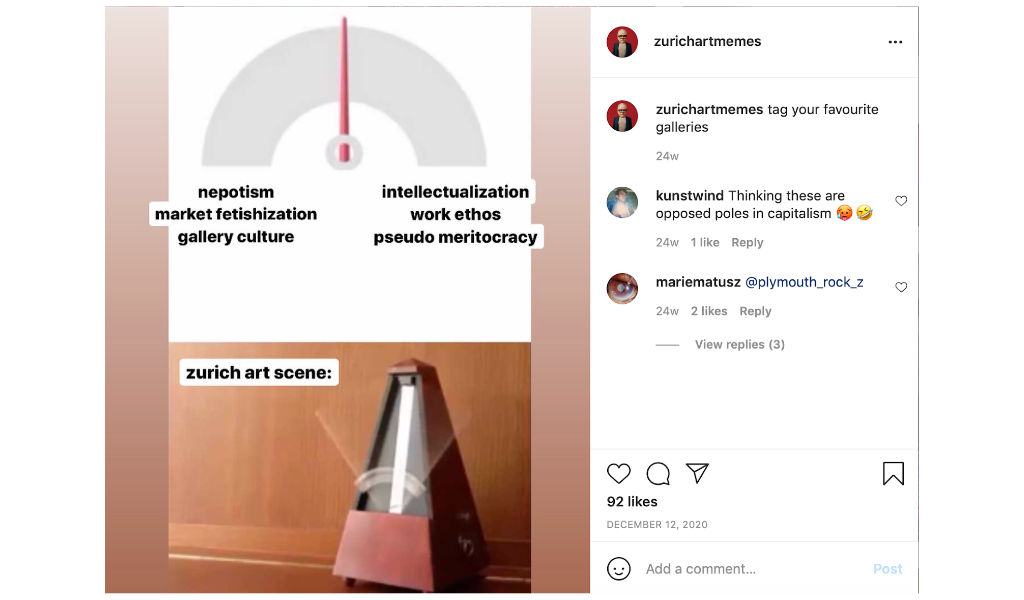

After all, with the spread of the We are the 99% meme, it was often artists, especially those side-lined by the established art world, who emerged as key organisers. I spontaneously have to think about Duncombes' comparison on the author as a producer: " Applying Benjamin's analysis to the case of zines. It is exactly their position within the conditions of production of culture that constitutes an essential component of their politics, " (17) since, in an increasingly professionalised culture-world, zine producers are decidedly amateur. With a double jump, this reference to Benjamin at the time Duncombes writes could be valid for a meme today as a medium of political expression and, at times, a means of protest, as confirmed by the anonymous author of the Instagram account Zurich Art memes in a text-only talk on zoom organised by RCS.

Paraphrasing Jean-Pierre Gorin's, "the point is not to make political art but to make art politically" (18). Despite the recent global appeal (appropriation?) of socially engaged and activist art, the art market remains a conservative system privileging individually authored object-based and conceptual approaches over daring collaboration. The next RCS protest will be organised in Basel on July 3rd, but the aim is to extend the network on a broader level, well beyond Switzerland's borders. What kind of hierarchies and tensions can emerge when emancipative initiatives are developed through the transnational cooperation of heterogeneous communities? Finding new ways to account for collective artistic value must also theorise the many occasions in which no object is produced or where the artistic practice is a form of creative engagement focused on the organisation's process, like in this case.

Definition of cultural capital would become broader (19) onto what might become a far more radical redistribution of creative value from high culture towards the dark matter beyond.

This activity necessarily points to the articulation of what theorists Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge call counter-public sphere: a fragmented realm of unconscious fantasy produced by workers in response to the alienating conditions of capitalism that "…has no existences as a ruling public sphere, for it has to be reconstructed from such rifts, marginal cases, isolated initiatives." (20). But at the same time, I would add, this also represents the counter-productive surplus familiar to the dark matter, characterised by its "contradictory nature" as a sporadic and spontaneous moment of resistance, rather than a means of sustained opposition.

The point I am trying to make is that a collective approach is recommended so that the Reclaim the Cultural Surplus motto becomes inherently part of each person's psyche more than a movement. Something able to build concrete manifestation of counter-public space to bring together numerous, otherwise fragmented forms of resistance while remaining networked and yet relatively autonomous concerning the high art world.

There are several models for young artists working collectively and addressing their relationship to labour. For example, Teaching Artists Union (21), whose founding manifesto begins with a statement of self-identification as a generation of "freelance idealists" before continuing heedfully, "we are not angry labourers." Similarly, RCS defines its art protest "in the spirit of Joyful Resistance" =) —> ?

With their fictional "sociological" documentary about creative industry workers just like themselves, Berlin-based Kleines postfordistisches Drama (KPD) has pinpointed the difficulty of being trapped in its feeble expectations about a "good life", where invisible surplus is not entitled.

That this missing mass, this dark matter, is materialising and getting brighter is not in doubt. Instead, what remains to be seen is how this "revenge of the surplus" will ultimately re-narrate politics.

Although I find the initiative of RCS very much needed, I'm not sure about the way forward yet. Until now, we have a poorly attended demonstration and an accompanying show that risks "presenting" the issue as a mere exhibition topic. "Criticising privilege becomes a privilege.", Theodor W. Adorno warns us (22). Changing production conditions within and around the margins of the contemporary art world and the resistance to those changes is a privilege we should embrace together with its critique.

#ReclaimCulturalSurplus Manifesto

Article edited July 3rd 2021.

(1) Gregory Sholette, Dark Matter: Art and Politics in the Age of Enterprise Culture (London: Pluto Press, 2010), p.3.

(2) www.artspaceguide.ch

(3) https://offoff.ch

(4) Marina Vishmidt, “The Aesthetic Subject and the Politics of Speculative Labour,” OnCurating Issue 48, 2020.

(5) Sholette, p.35

(6) Benjamin Noys, George Bataille, A critical introduction, 2000, Sterling, London.

(7) Slavoj Žižek in It's the Political Economy, Stupid. The Global Financial Crisis in Art and Theory. Professional & Vocational, by Sholette, GregoryHrsg.Ressler, OliverHrsg.

(8) Carol Duncan, The Art Museum As Ritual, Civilizing Rituals: Inside Public Art Museums, Routledge, 1995.

(9) https://www.marxists.org/glossary/terms/s/u.htm.

(10) Gregory Sholette, Delirium and Resistance: Activist Art and the Crisis of Capitalism, Kim Charnley (ed.), London: Pluto Press, 2017, p.38.

(11) HyperNormalisation. 2016. [film] Directed by A. Curtis.

(12) “The antidote to civilisational collapse: An interview with the documentary filmmaker Adam Curtis”, Open Future, The Economist, Dec. 6, 2018, accessed Dec. 29, 2018, https://www.economist.com/open-future/2018/12/06/the-antidote-to-civilisational-collapse.

(13) Sholette, Ibid. p.63.

(14) CERN, accessed May 27, 2020, https://home.cern/ science/physics/dark-matter.

(15) Lucy Lippard, ‘Foreword: Is Another Art World Possible?’, 2018 in G. Sholette Activism against Nostalgia and Self-Defeatism: Gregory Sholette, Delirium and Resistance. Activist Art and the Crisis of Capitalism, p.17.

(16) G. Sholette, Ibid., p.73.

(17) from a 1994 issue of the zine Riot Grrrl, cited in the book by Stephen Duncombe, Notes From Underground: Zines and the Politics of Alternative Culture (London, Verso, 1997), p. 123.

(18) Gretchen Coombs, The Lure of the Social: Encounters with Contemporary Artists, p.24.

(19) First used by French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, the term Cultural Capital can now be widely found in the literature of cultural policy think tanks and even economists albeit stripped of its original, class conscious social critique.

(20) Public Sphere and Experience Analysis of the Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere by Alexander Kluge and Oskar Negt, 1993.

(21) http://teachingartistunion.org, last access 1.07.21.

(22) Fabian Freyenhagen, in Adorno's Practical Philosophy: Living Less Wrongly, Cambridge University Press, 2013.

ESSAY

Giulia Busetti - June 2021

The Reflecting on... series takes situations, objects, artworks, articles, texts, podcasts and anything else really as starting points for reflection on artist-led and self-organised (AL&SO) practice.

The Reclaim the Cultural Surplus! Art protest in front of Kunsthaus, May 8th 2021.

The Reclaim the Cultural Surplus! Exhibition view, OnCurating Project Space, 2021.

Ephemeral Care focuses on ethics, practice and strategies in artist-led and self-organised projects.