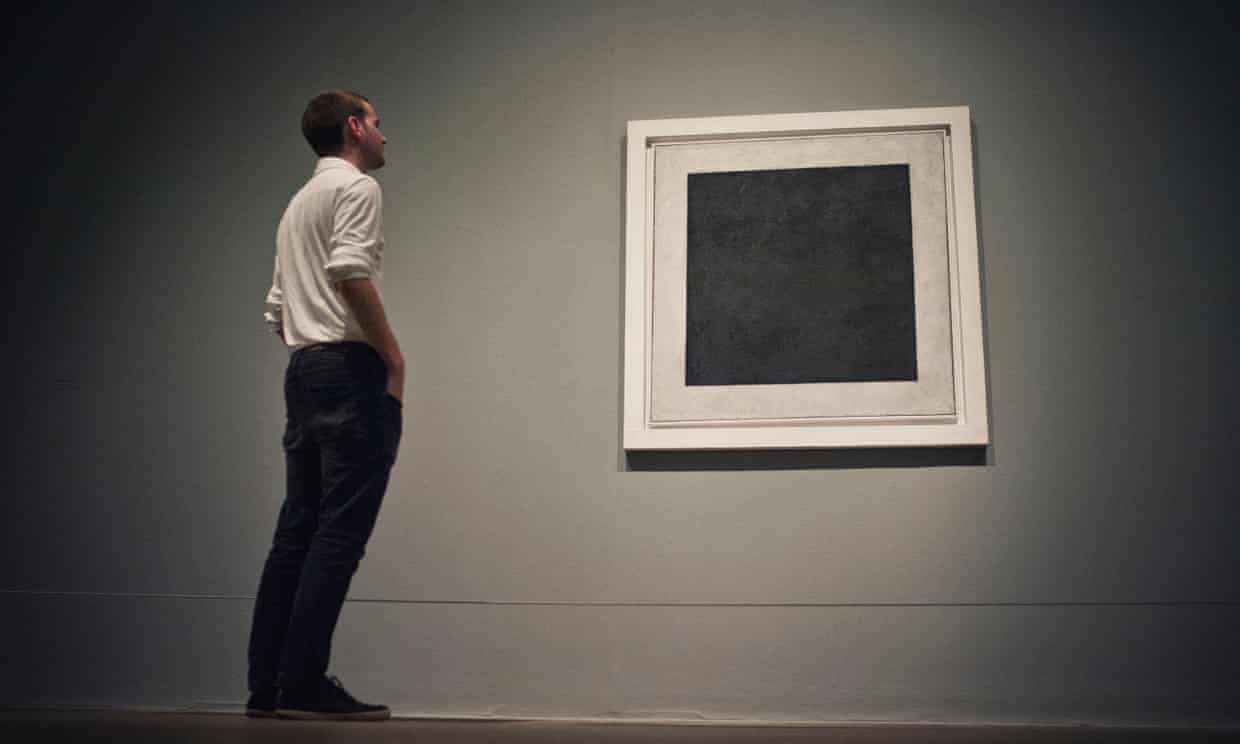

Black Square. Kazimir Malevich. 1915

But that night, the 24th of July wasn’t the 80s. It was now. Yes, we’d been drinking and perhaps spending the night engulfed in fervently African festivities had filled us with a false sense of freedom as we sauntered into Hornstull Station. We had already reached the platform when we were stopped and Kamaru was quickly taken into custody by what appeared to be guards acting on behalf of some corporate or state entity. Through the panic, hopelessly asking other passengers and employees for help, I didn’t reach for my phone. At that moment, I thought this little black box couldn’t help my friend. They didn’t hurt him and they released him less than two hours later. I felt so bad but he seemed fine and used to it. So did everyone else. I keep asking myself if I was seeing something that wasn’t there.

I first encountered the black square as an undergrad at Michaelis School of Fine Art around 2005. I actually really loved it. I was attracted to its abstraction as it seemed to reflect me most fully. But it seemed the abstract in fine art was still generally reserved for whiteness. Black kids like me only did well when they made portraits. Bonus points for self portraits in the style of fashion photography - an obvious contraption for the performance of black identity. Perhaps they were perceived as inherently more complex, but my white classmates excelled when they dabbled in the abstract, while the same lecturers insisted my attempts looked like a “mess on the studio floor”.

Nevertheless the black square followed me and I asked myself if the Russian artist Kazmir Malevich, like myself, felt underwhelmed and imprisoned by realism. The artist's statement that Suprematism (an abstract genre he created) represented “the supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts” seduced me into thinking here lay a liminal space in which even I could come as I am. The 1915 work Black Square by Malevich with its avant garde swag and formless flair kept me enthralled. Ten years later while analysing the painting under x-ray, scientists discovered that underneath the black paint was a layer of text that revealed a sinister racist joke.

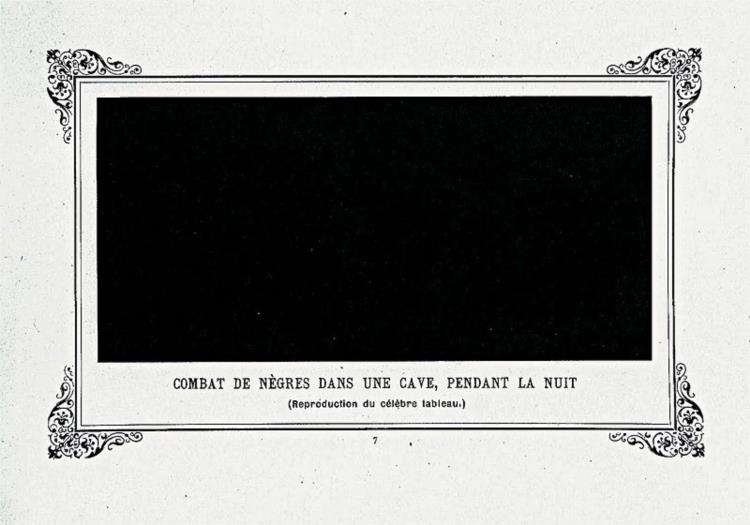

The text read: ‘Negroes battling in a cave’ which many believe was based on an earlier French work by Alphonse Allais in 1897 which was also a black square entitled: ‘Negroes Fighting in a Cellar at Night’. If you’ve spent as much time around white people as I have, racist jokes don’t phase you. And if the joke were as simple as ‘you can’t see blacks in the dark’, well that would have been just another day at the office. The problem is how close I got to the work. How hard I looked. I looked so hard I thought I saw myself. Myself through the eyes of someone that (jokingly) does not see me. How dark is that?

Negroes Fighting in a Tunnel by Night. Alphonse Allais. 1884

Even now as I navigate Stockholm as a member of the African diaspora, I am seldom asked about my own lived experience or African culture as it exists here, but about the looting, the killings, the mobs, the pandemic. Although black culture is moving into the mainstream, the price for this triumphant presence is an evasive erasure of black life, love and joy. Presently and historically, some of the most iconic black narratives and images are sensationalised by brutality and death.

Emmett Till, the 14-year old African American who was lynched for allegedly offending a white woman in 1955; posthumously became an icon of the civil rights movement. 13-year old Hector Pieterson’s lifeless body, held in Mbuyiso Makhubo’s arms as he and Pieterson’s sister Antoinette Sithole fled towards the photographer Sam Nzima’s car. This image would become a universal symbol for the 1976 apartheid uprisings. Then there’s Steve Biko and Malcom X, who spoke passionately against the public consumption of violence against black bodies - both ironically canonised in public images of their own brutalised corpses.

Social media amplifies this frenzy, particularly during the ongoing pandemic. Take the #blackouttuesday hashtag, organised within the music industry on the 2nd of June 2020, which was a response to the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, general racism and police brutality. While people from all walks of life saw it as an opportunity to raise their hands and absolve themselves from racism, many aspects of the collective action left much to be desired. It was like cringingly watching people collectively give to charity and then post pictures of it on social media. The giving was undeniable, but the beneficiary was debatable.

When activists on the ground called for users to stop using the BLM hashtag as it blocked information which was necessary for them to organise on the day, they were met with more black squares. The whole thing reeked of censorship and recalled me to that historical joke -’we don’t see you’. Days after the hashtag had happened, social media users and influencers across the world openly insisted on using the n-word and blackface to show their version of solidarity with the black lives matter movement.

During #blackouttuesday South African musician Nakhane Toure observed: “Seeing the same white people who fight you tooth and nail when you call out their microaggressions posting that black lives matter and they stand in solidarity blah blah.. “ British-Barbadian saxophonist Shabaka Hutchings added: “The idea behind the black square was opening a space to learn and mobilise but posting a black square can’t be the only act of solidarity. With very little effort, it’s just another exercise in self aggrandisement”.

At this point, we probably did need #blackouttuesday and it makes sense to use an image to carry such sentiment. The use of the black square managed to encompass black suffering without veering towards the grotesqueness of the photograph. Nonetheless its resemblance to the evasive vision of the aforementioned abstractionists is eerily timed. As Europe swerves once more to the far right and in a time when stories and images travel faster than ever, black danger and death cannot remain as an inevitable, casual truth. This is how we may be seen (or not seen), but it need not be how we see ourselves.

ESSAY

Heidi Sincuba - AUG 2021

The Reflecting on... series takes situations, objects, artworks, articles, texts, podcasts and anything else really as starting points for reflection on artist-led and self-organised (AL&SO) practice.

Heidi Sincuba

@heidisincuba

www.heidisincuba.com

Thembeka Heidi Sincuba (they/them) began undergraduate studies at the University of Cape Town and Artez

Arnhem going on to do a masters at Goldsmiths University of London and is now a PhD candidate at the

University of Cape Town with a working thesis title: Ubungoma, Fetish and Technology: A Synthesis of Art.

The artist has taught painting at Rhodes University as well as a course called Spirituality in Art at the University

of Cape Town. This research interest is rooted in the artist’s own training as a sangoma (Traditional Healer).

Sincuba’s creative practice uses the concepts of Afro-pessimism and social death, with an interest in womxn’s

work globally and more specifically sub saharan Africa. The work’s aims are towards fugitivity, sex positivity and

the eradication of gender based violence. The transdisciplinary use of painting, drawing, photography, video,

performance, text, textiles, community work and installations, as well as a conceptual foundation of lived

experience and indegenous knowledge systems mark the nuance of this practice. The decade-long, independent

career has yielded a fluid and speculative aesthetic, manifested through methodologies of multiplicity.

Ephemeral Care focuses on ethics, practice and strategies in artist-led and self-organised projects.